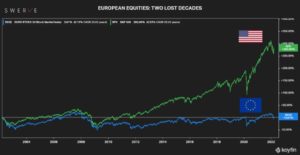

European equities: the lost two decades

European equities return over the last twenty years was an abysmal 3.9% vs 282% for the S&P 500 (see chart). The next decade looks, if anything, even more problematic as the Ukraine war delivers continental Europe a severe economic, financial and geopolitical blow.

European equities return over the last twenty years was an abysmal 3.9% vs 282% for the S&P 500 (see chart). The next decade looks, if anything, even more problematic as the Ukraine war delivers continental Europe a severe economic, financial and geopolitical blow. Russia was the EU’s largest trade partner and the primary provider of strategic commodities. Rearranging energy supply will be very expensive and it will hamstring Europe’s competitiveness for years to come. The EU was also the largest foreign investor in Russia and balance sheet losses will mount over the next weeks and months. On the banking side only, the BIS estimates $82 bil due to EU institutions. Geopolitically, the war makes continental Europe ever more fragile and dependent on the US, not only for LPG but also, more critically, for defense assistance and imports. With a likely 2022 print in the high single digit, inflation will be a problem for years and economic growth, already sluggish before C19, will be elusive. Policymakers’ options to deal with the ensuing stagflationary environment are precious few and all problematic. On the fiscal side, yet more deficit expansion seems inevitable to offset the Ukraine-induced hardship. A continental-wide Rooseveltian “new deal” is unlikely given that fiscal policy is prerogative of the single member states and intensely political. It is not just about money, it is the “operating system” of the various members that is not compatible. You simply can’t turn Italy or Greece into a Germany or Austria. On the monetary side, the ECB’s hands are tied as they have no way to fight inflation without crashing uber-indebted countries. On the contrary, they will have no other option but to further expand the balance sheet and to serve as lender of last resort. Hence propelling inflation even higher. Herein lies the key issue; the eurozone was never designed to function in a stagflationary environment. Inflation is effectively a transfer of resources from one member country to another. Whereby the fiscal deficit of one country is paid for by all the other members by means of the devaluation of the common currency. The incremental debt created to fund early retirement in Greece or Spain, for example, is disproportionately covered by debasing the savings of those more frugal member states with lesser fiscal deficits. Inflation ravages both savers and the more vulnerable strata of the population and breeds discontent; as politically-driven social spending accelerates, fiscally stronger countries will balk at the hardship of rising prices. A showdown will ensue and markets will recoil as virtually no one is positioned for the restructuring of the currency union. There may be a time ahead where European equities will start to make sense but we are not there yet. Investors keen to deploy capital in Europe may want to wait for the dust to settle before searching the rubble.